Vietnam et France: L’Histoire Perdue

The current PBS presentation of Burns’ and Novak’s Documentary on the Vietnam War, has reawakened the public interest in Vietnam and the Vietnamese-American War. Episode 1, presents a brief history of the French colonial period and the French Indo-china war that preceded the American involvement.

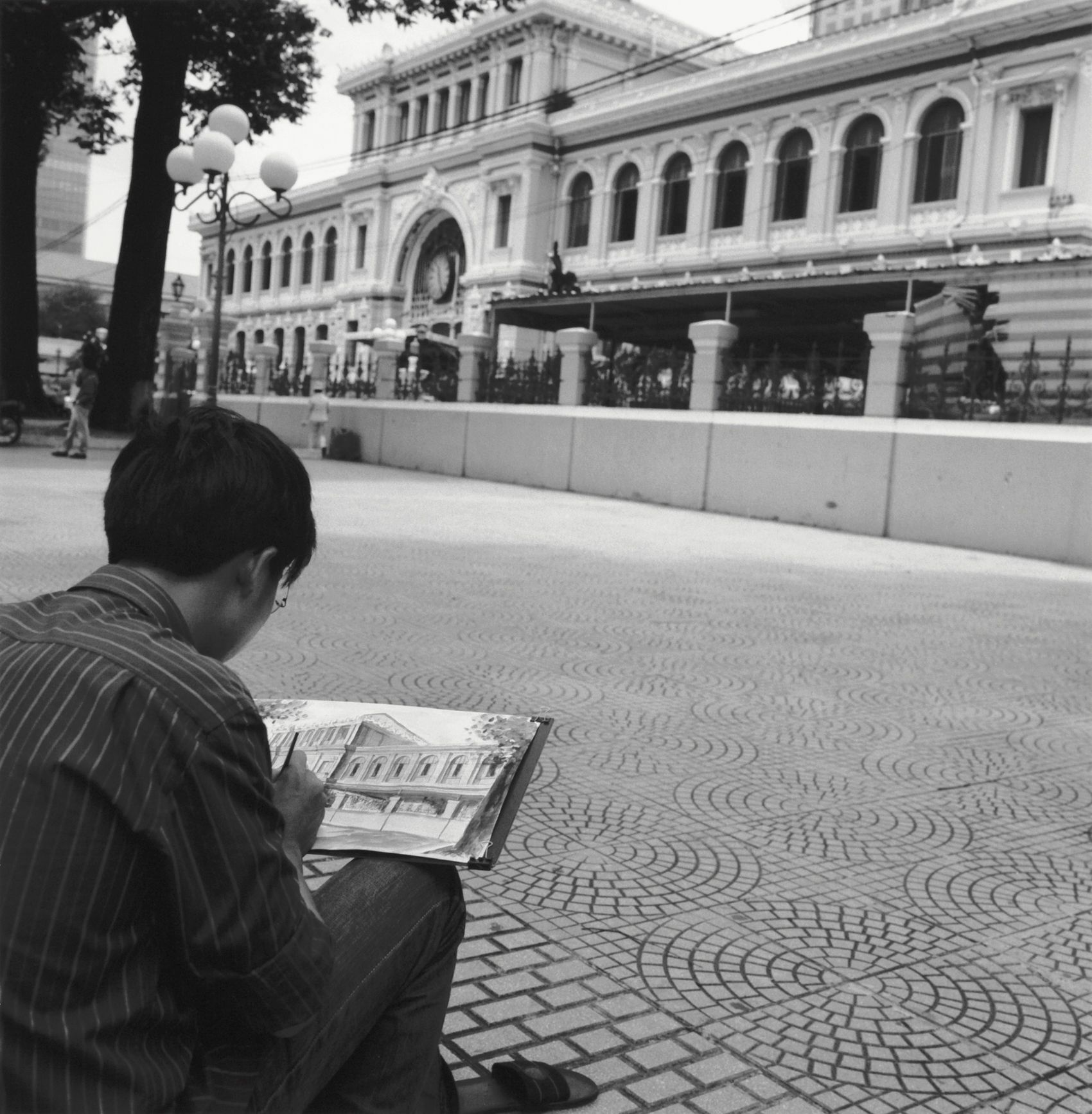

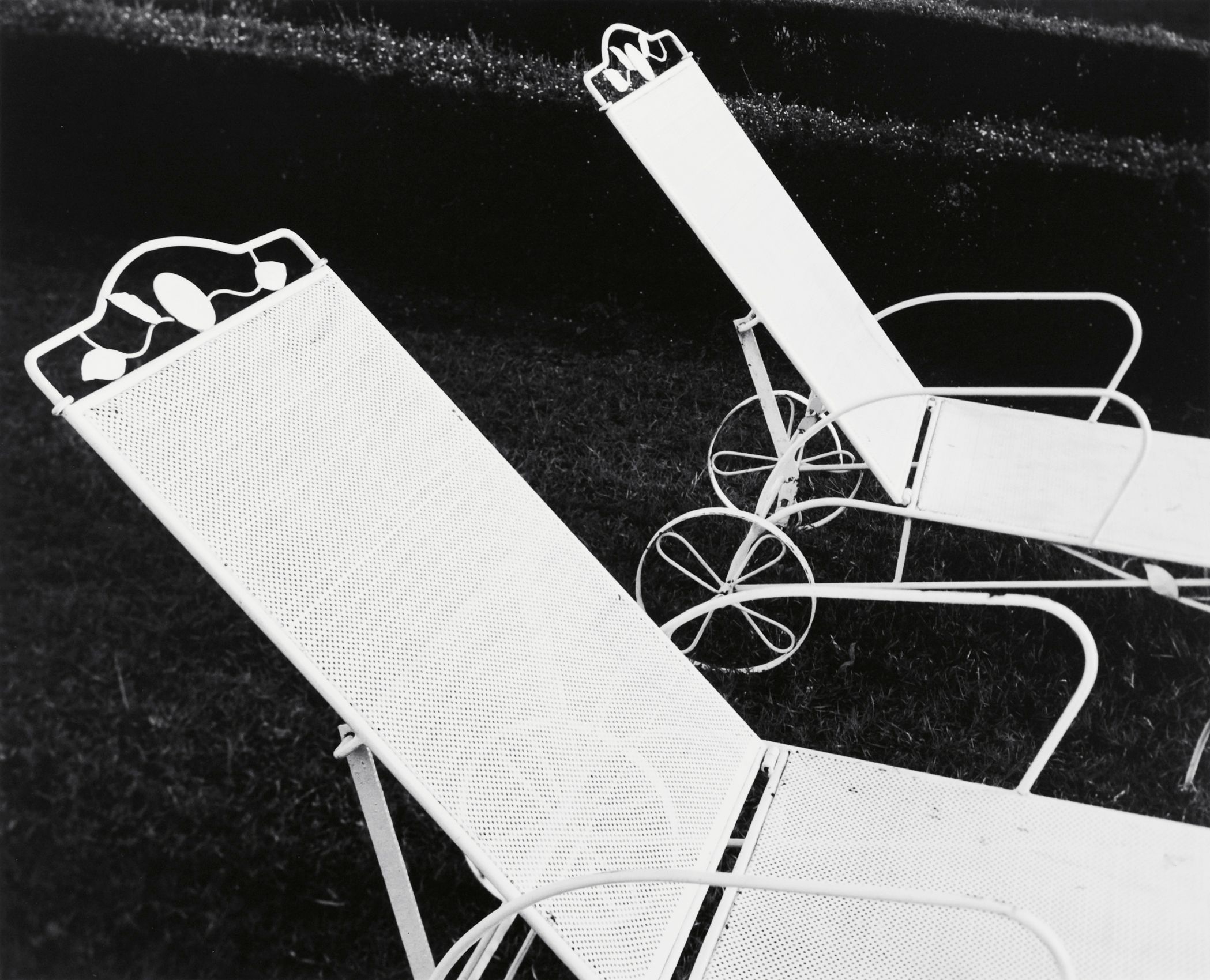

The title of this Portfolio has several meanings. On the first level, it refers to the physical elements contained in the photographs, which I created during a series of visits to Vietnam over a 6-year period. I searched for the French colonial legacy as it exists today. This legacy goes back to the first French Jesuit missionaries and traders who went to Vietnam three centuries ago. It covers the period starting in the nineteenth century when France first invaded Vietnam, the French withdrawal from Vietnam in the mid-twentieth century, and the devastating wars for independence.

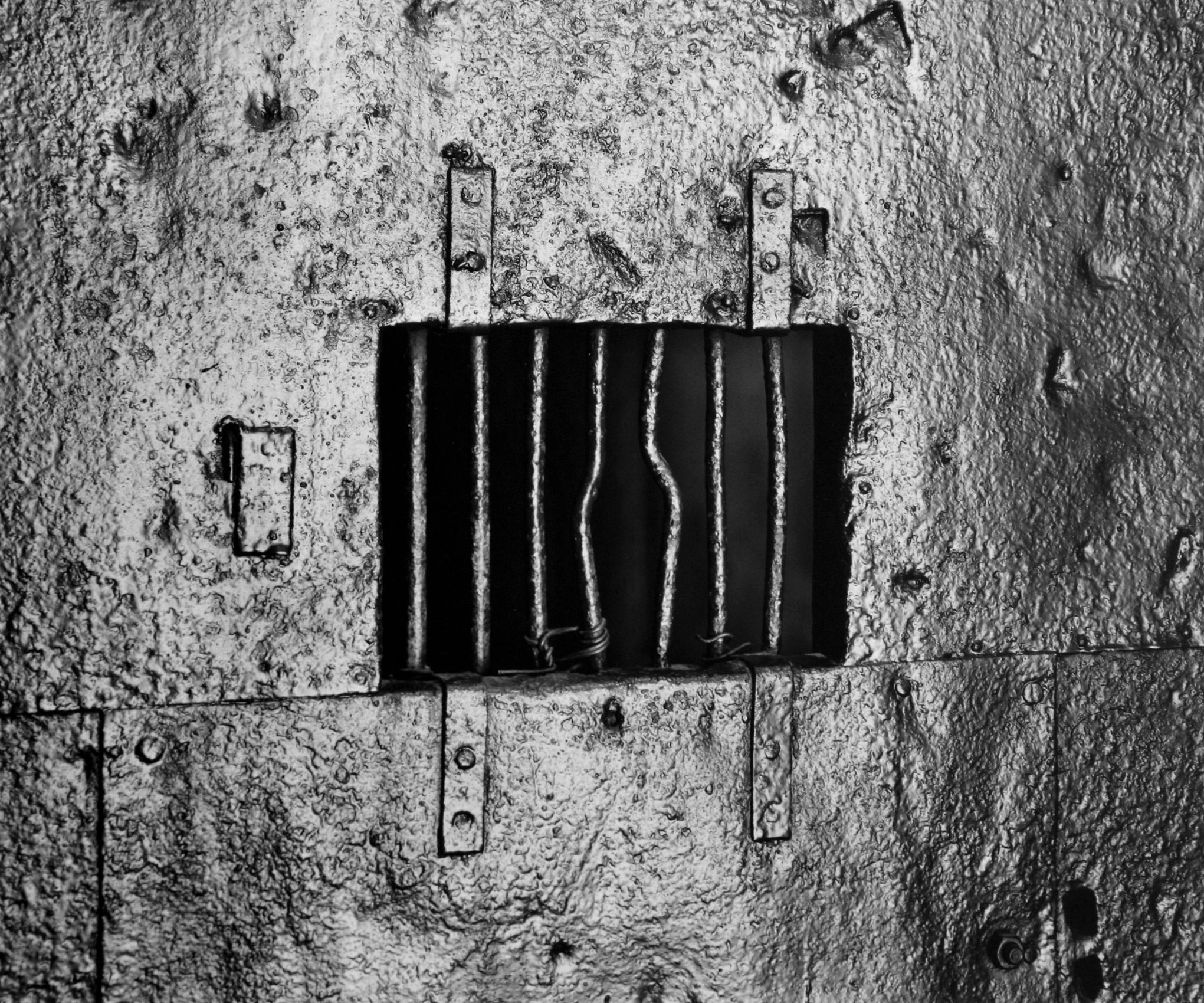

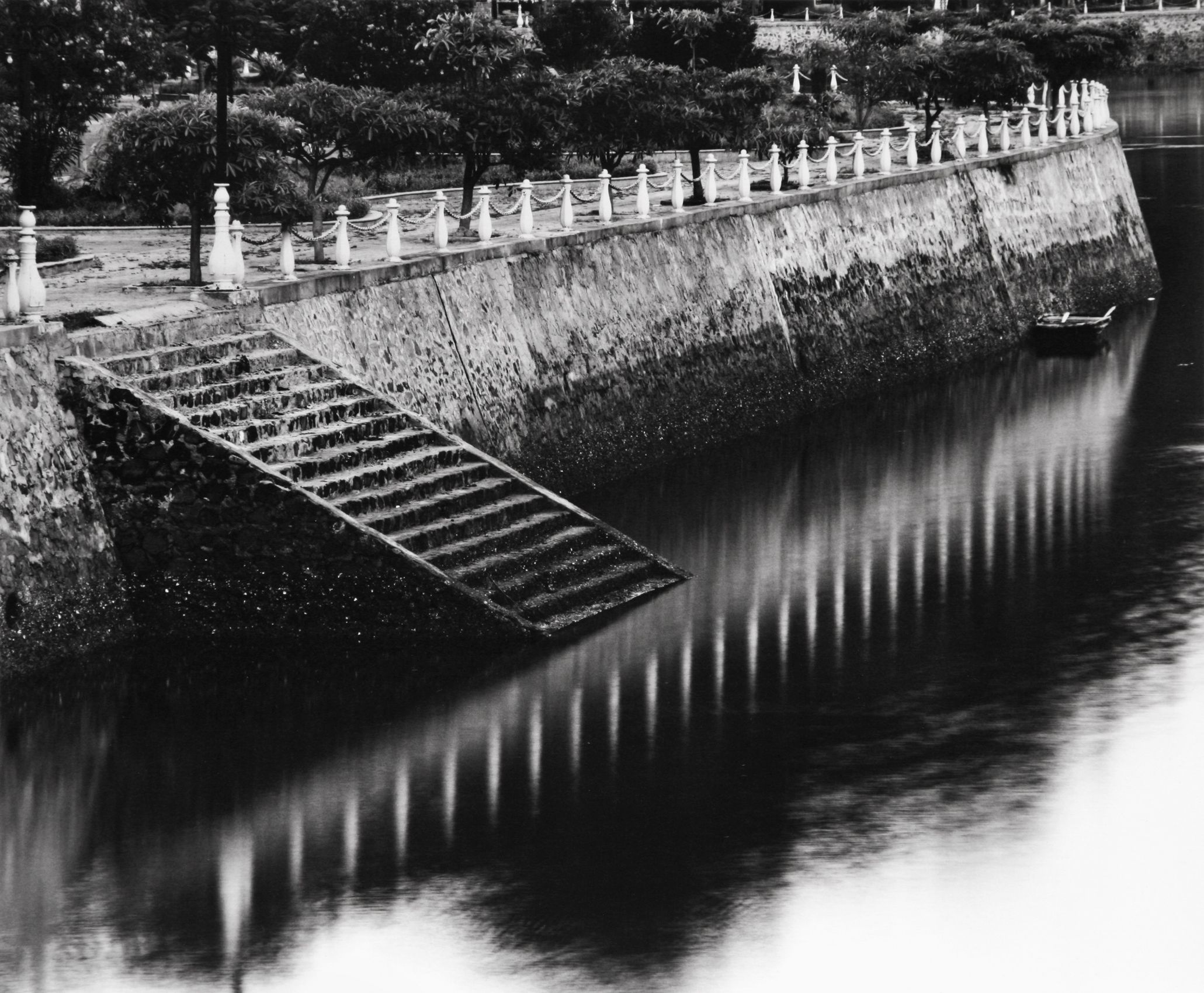

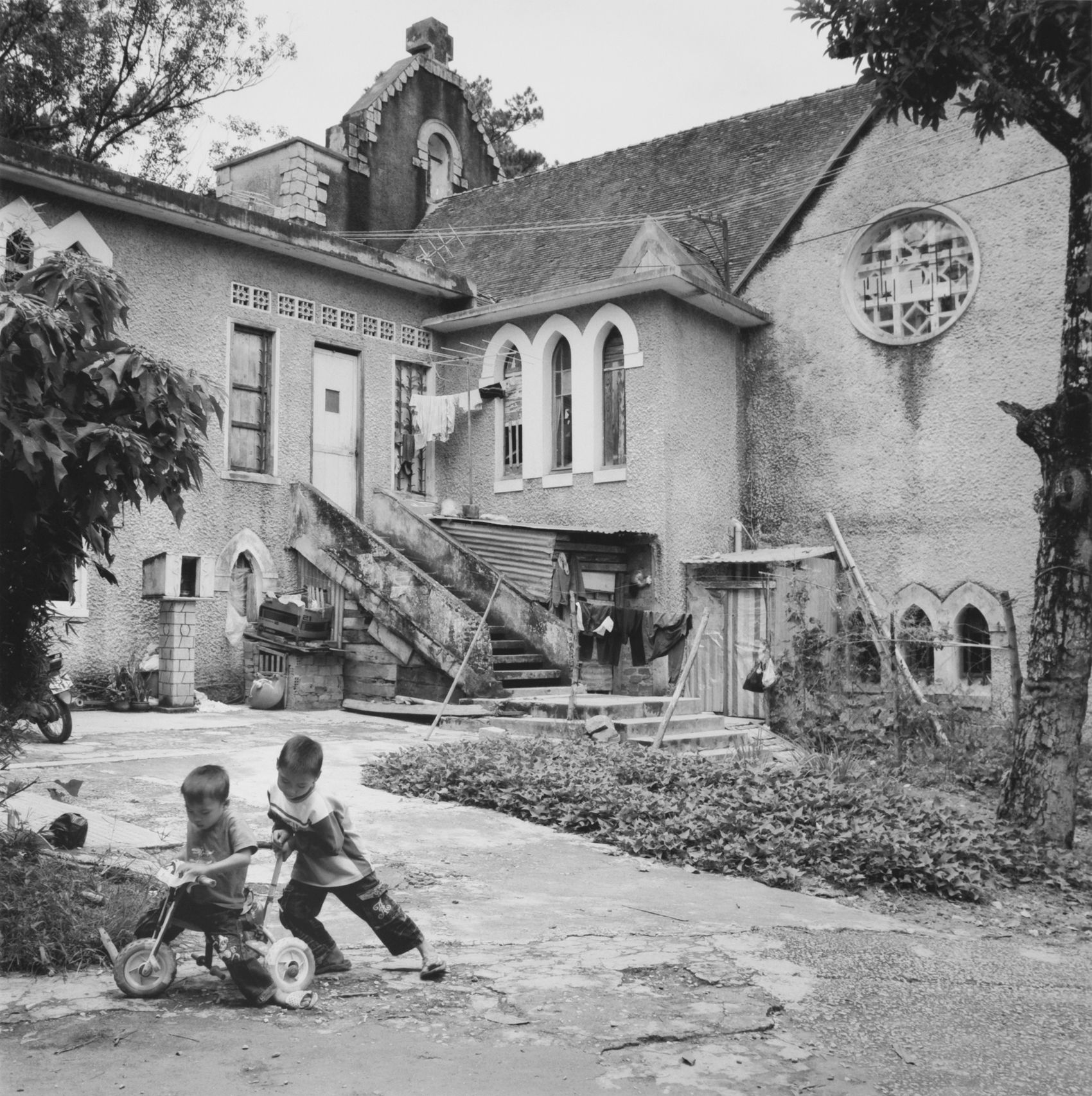

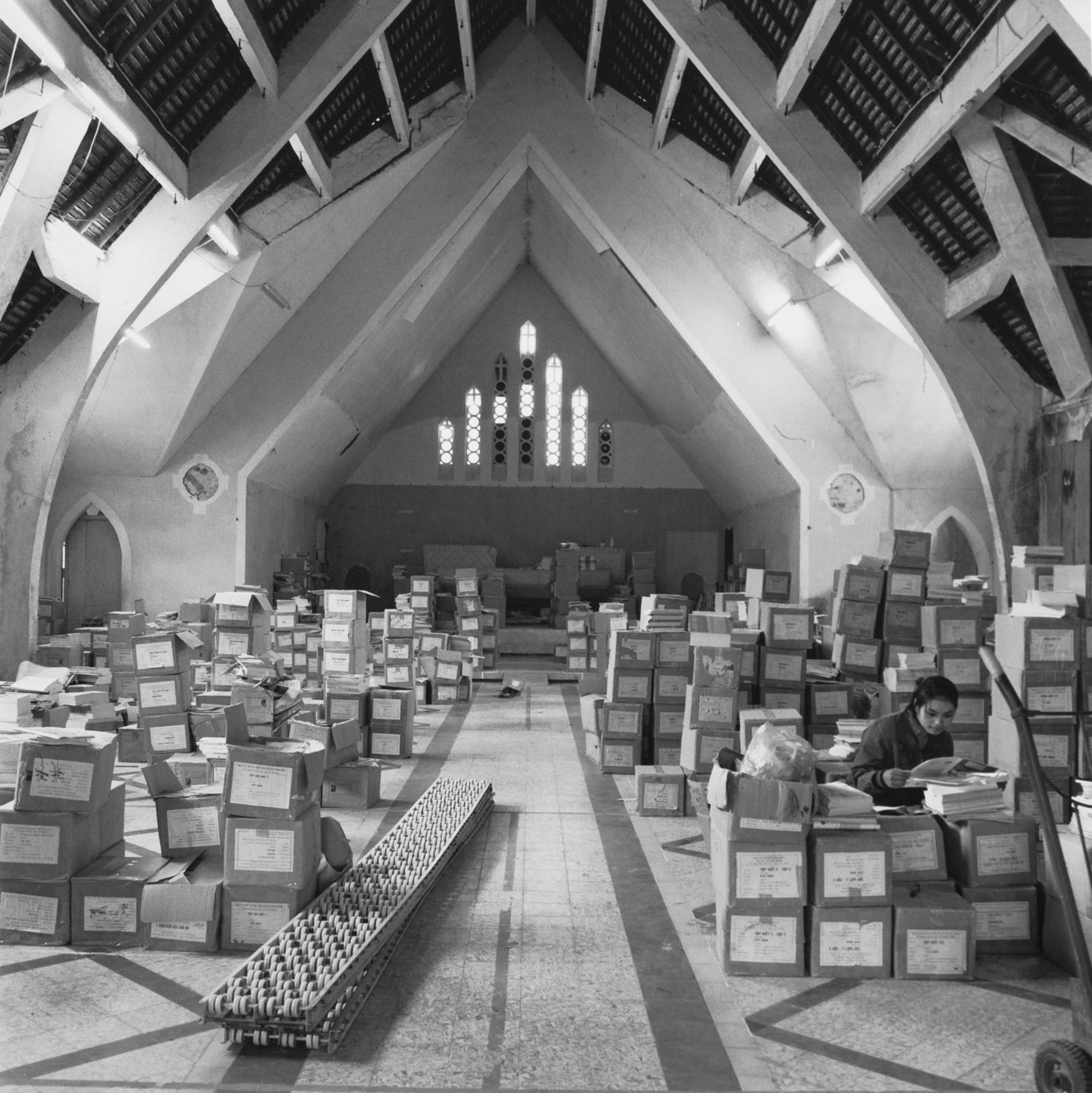

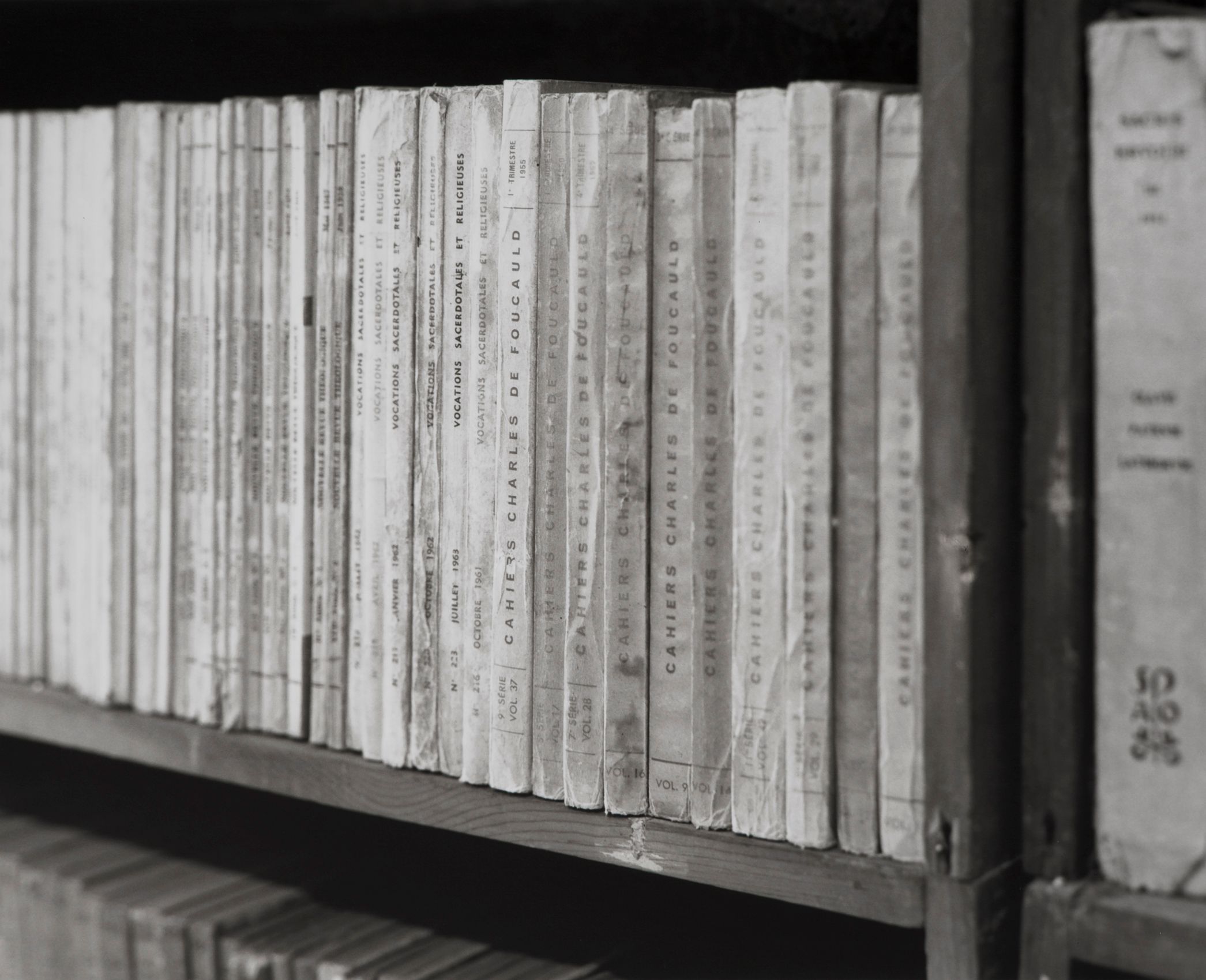

What is most surprising is that 21st Century Vietnam continues to rely on the underlying infrastructure created during the French colonial period. In the major cities of Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC - formerly Saigon), Hanoi, Haiphong, Nam Dinh, and those in the Mekong Delta and the Central Highlands, layouts of the streets, the parks, and the municipal buildings are of French design. Furthermore, the French left behind hospitals, churches, seminaries, schools, libraries, research institutions, prisons and courts, residential buildings, as well as a transportation infrastructure which includes roads, trains, ports, lighthouses, bridges, dams, dykes, and irrigation systems. While their work took place within the framework of a colonial system that used French architecture and know how, the Vietnamese people contributed the physical labor.

Today, many of the largest and most beautiful colonial buildings have been transformed into Vietnamese government buildings, museums, embassies, hotels, restaurants, travel agencies, and residences. Yet in HCMC and other thriving cities, colonial buildings are being replaced at an alarming rate. Decay and development are literally washing away history. Photographing the remaining material evidence of this period is at the heart of my project. Similarly, within the population, only the oldest people still have any memory of the French period, and few still speak French.

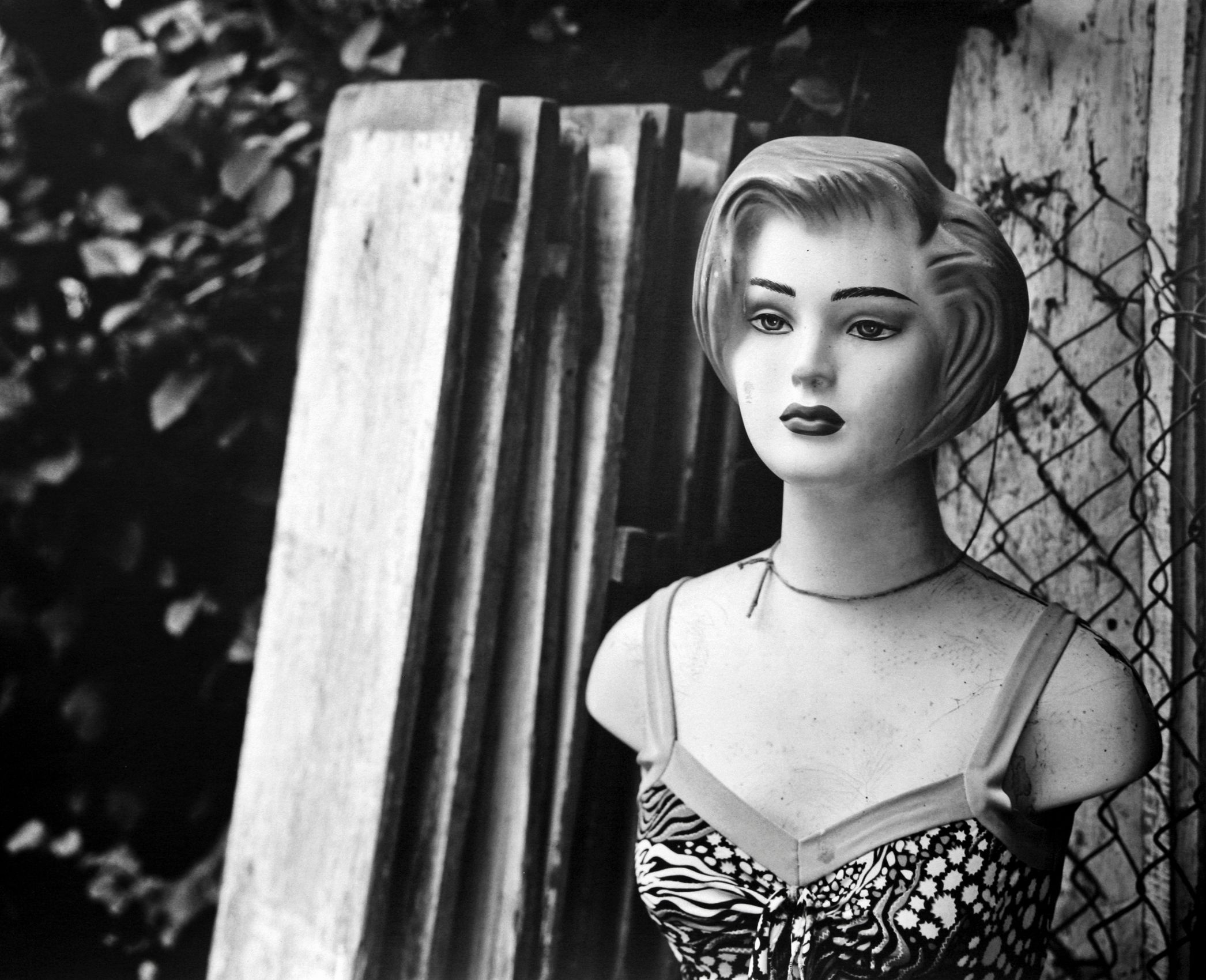

As a photographer, the more I know about the history, the better I am able to peel away physical and cultural layers and discover a country’s past. In certain places the history is self-evident, while in others it is obscured. The jungle overruns buildings, making seventy-year-old ruins seem as ancient as Roman aqueducts. Through all of this, I find myself becoming part-archeologist, part-explorer, part-journalist, and part-artist.

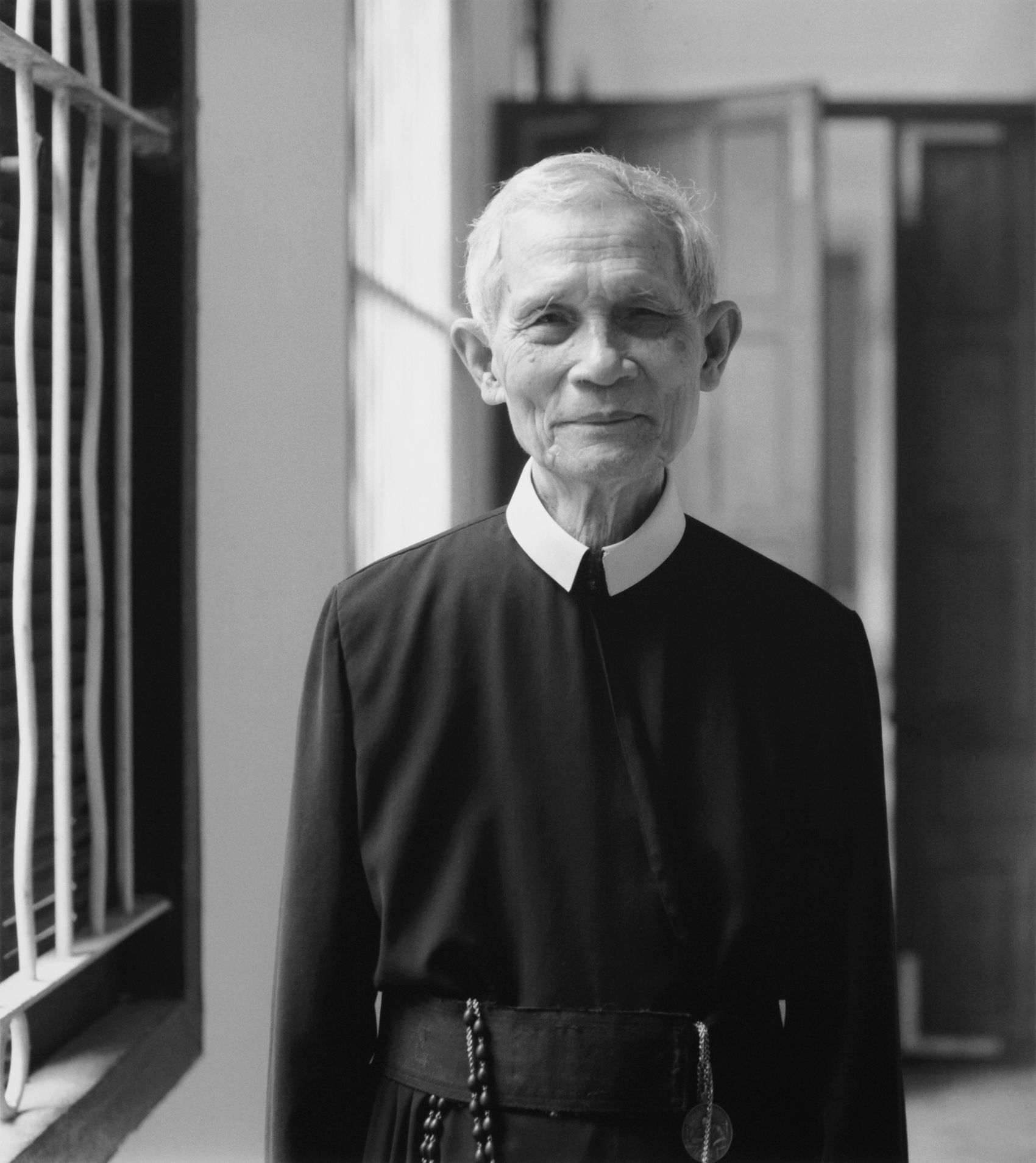

On another level, the title refers to the lost histories of the peoples who lived during these past times, including French, Vietnamese, and those in-between. What I mean by those in-between refers not only to those of mixed descent, but also to people from both races and cultures who adapted to the other culture. Think of the families from France who lived in Vietnam for several generations. Would the offspring born there still be entirely French? Or how did the Vietnamese who attended French lycées or the new universities in Hanoi, Dalat, and elsewhere assume a part-French identity? Likewise, to what extent did the Vietnamese priests trained at the seminaries or the Vietnamese soldiers who fought for France during WW I become “Frenchified”? Where are their histories?

Lastly, and perhaps the most complicated, is the lost history that never happened. In theory, France with an ethos based on the revolutionary principles of 1789--“Liberty, Equality and Fraternity”—should have been less exploitive rulers than the English, Spanish, and Portuguese in their respective colonial empires. However, in the actual task of ruling Vietnam, this was mitigated by several very important factors: first, the pervasive institutional racism toward non-white people, which was particularly vexing to the Vietnamese with their proud 1000-year old culture that has long fought outside hegemony, primarily Chinese. Furthermore, the policies that France used as a framework for ruling Vietnam were applied in a bureaucratic fashion from a larger set of regulations created to be used throughout its colonial empire, and were not ideally suited for the conditions in Vietnam. Unlike colonies such as those in Africa or the South Pacific, Vietnam had a long tradition of an educated elite class (Mandarins). However, this class was kept very small due the difficulties of learning the Chinese written script and the rigors of the Confucian testing system. With the creation of the Latinized or Quoc Ngu script, developed by the Jesuits in the early 17thcentury and popularized from the late 19thcentury onward, a larger urban educated class developed. It is obvious in retrospect that this educated population would eventually resist the subservient role imposed upon them by a hierarchical colonial system. And, indeed, this culminated in a series of mass uprisings led by both nationalistic and communistic organizations that began in 1930. This was the start of a 50-year struggle for Vietnamese independence. Furthermore, major geopolitical events of the 20th century--namely, the rise of modern Japan, World War II, and the capitalist/communist ideological confrontation—conspired to place Vietnam at the center of global hostilities. Divorce became inevitable, despite what this traveler feels is a deep-seated sympathy between the two nations’ cultures.

The photographs for this project were all taken using medium format (120mm) film. The cameras used include a Linhoff 4x5, Hasselblad and Voigtlander Bessa 2 and Agfa Rangefinders. With the exception of the Hassleblad images, I used exclusively vintage lenses from 1930-1960, which, combined with black and white film and traditional darkroom printing, create images that best evoke the era. My photographs attempt to capture mood as well as physical space. I want each piece to be a small poem, but the series as a whole to tell a narrative—a narrative that is sympathetic to both the Vietnamese and the French. And while this project focuses on the past through the choice of locations that I searched out, I also want to show how this past continues into the present and into the future.